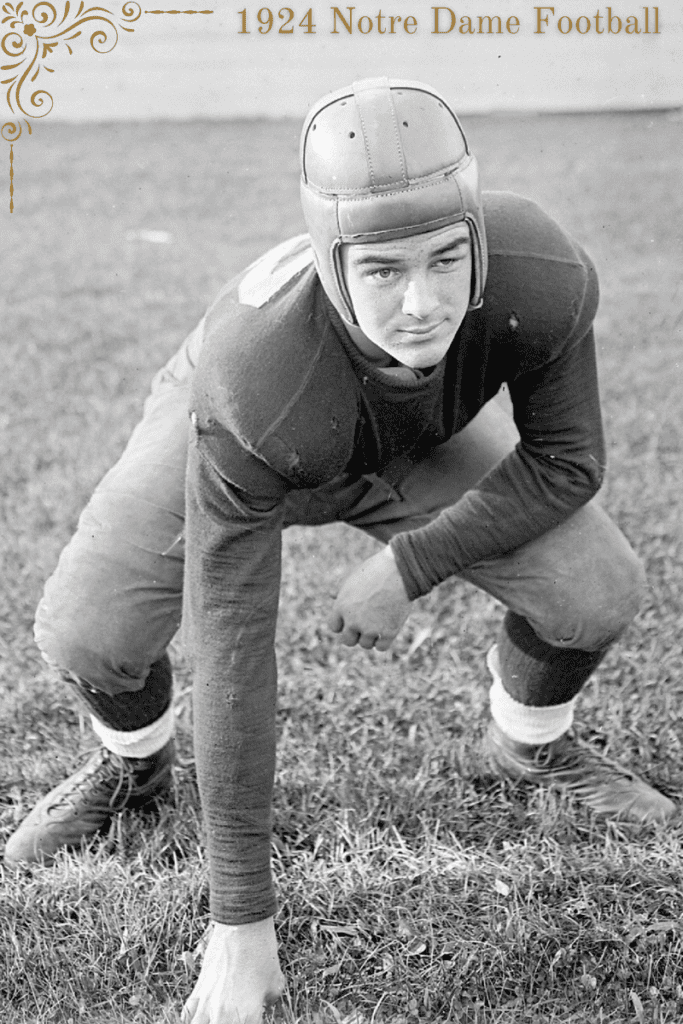

John Weibel

Left Guard

Erie, PA

The Nov. 11, 1922 meeting between Notre Dame (6-0) and Army (6-0-1) was an emotional, all-out physical battle between two top teams. The crowd that ringed Cullum Hall Field at West Point, N.Y., surged toward the fevered action. In fact, it would be the final game at that location, as the rivalry had outgrown West Point and would be headed to New York City the next season.

Every few plays, it seemed, one player or another would be laid out on the turf. In many cases, they would shake off their injury and continue. Some were not so lucky.

Late in the first half of the scoreless tussle, it was Notre Dame’s outstanding left guard Harvey Brown who was writhing in pain. He was examined by a doctor and had to be carried off the field; his day leading the Irish line was finished.

Coach Knute Rockne turned to a little-used sophomore, John Weibel, to take over for the sturdy Brown. And young Weibel more than held his own the rest of the way, as the teams traded parries but failed to cross the opposing goal line.

In the final minute, Army lined up for what would surely be a winning field goal. “The Irish charge pushes the Army line back into the path of the kick. Blocked!” read one description. Final score: 0-0.

Rockne surely saw something of himself in Weibel. At just 5-foot-9, 165 pounds, he was nearly identical in size. A clever lad, he was a serious student of the sciences, with an eye toward medical school. Football became a welcome release from the pressures of the classroom.

Back in Erie, Pa., the player’s father, Dr. Elmer Weibel, had been practicing medicine since 1899, and was the city’s first radiologist and pathologist. The family lived in a fine home just west of downtown Erie.

The following season, Harvey Brown served as captain of the Irish, and again Weibel was at the ready as his capable backup. And with Brown graduated in 1924, Wiebel was the easy choice to take over his spot. As the Irish backfield had been dubbed The Four Horsemen, the line picked up its own moniker: The Seven Mules.

After the 10-0-0 season that earned the team the national championship, the Scholastic wrote: “Weibel is regarded as one of the greatest linemen ever developed at Notre Dame. His work on the offense was a mighty factor in paving the way for the fleet Irish backs. He formed with Noble Kizer and Adam Walsh one of the most powerful center trios that has ever worn a Notre Dame uniform. His defensive playing bespeaks a stout heart and his courage never faltered in the face of line plunges by mighty backs.”

In the fall of 1925, each one of the Horsemen and Mules had become college football coaches. Weibel’s path took him to Nashville, where he entered medical school at Vanderbilt and was eagerly welcomed to the school’s football coaching staff. (A decade earlier, Rockne had been accepted into medical school at St. Louis University, but wasn’t allowed to continue coaching football, so instead took Notre Dame’s offer, which included coaching football and track, in addition to teaching prep-school chemistry.)

Weibel, it was said, “comes to the Commodores bearing the enthusiastic commendation of Knute Rockne. Weibel was highly praised for his ability as a player and for the great work in tutoring spring practice, in which work Weibel was used as an assistant coach.”

As an assistant and scout for long-time head coach Dan McGugin, Weibel helped Vandy continue its string of highly successful seasons, going 6-3 in 1925 and 8-1 in 1926, with wins over Texas, Tennessee, Georgia and Georgia Tech.

In 1927, when Irish teammate Elmer Layden became head coach at Duquesne in Pittsburgh, Weibel joined him as assistant. After the season, he returned to Vanderbilt to complete his course in medicine.

In early 1931, 26-year-old Weibel was nearing completion of his medical internship at Pittsburgh’s Mercy Hospital. Life was good. A local athletic banquet welcomed Kizer, now the head coach at Purdue. “Weibel was the life of the party that evening, exchanging his customary witticisms with Kizer to the great delight of those present,” a report said.

The next day, Weibel was stricken with appendicitis. Complications occurred and on Feb. 17, he died of peritonitis. “Dr. Weibel failed to rally from an operation for appendicitis,” noted a Pittsburgh newspaper. “Fellow physicians made a gallant fight to save his life, three remaining constantly at his bedside when his condition became grave.”

“His death,” the paper continued, “marked the first break in the ranks of the eleven which carried the names of Notre Dame and Knute Rockne from coast to coast.” And it was an eerie precursor of what was to happen the following month in eastern Kansas.

“I am sorry to hear of the death of Johnny Weibel,” said Rockne. “He was a fine, clean boy, a good student and a loyal friend, and he had a fine career ahead of him.”

Kizer called Weibel “one of the greatest pals I ever had—to his memory, I can pay only the highest of tribute. As a companion throughout my collegiate days and as a true friend since, he had earned my highest admiration and respect.”

At the funeral in Erie, among those bearing the casket were Layden, fellow Horseman Don Miller and Mules Walsh and Joe Bach. “Beside the casket of their former teammate, these four bowed their heads in sincere grief and unhesitating tears came.”

His funeral was called “probably the largest ever given a layman in this city.” Nearly two dozen interns of Mercy Hospital, paying homage to their fellow doctor, marched at the head of the funeral cortege. Weibel was eulogized for his character and accomplishments.

For his Notre Dame teammates, little could they have imagined that they’d be gathered just a few weeks later to bid goodbye to their beloved coach.

(This profile appeared in the Irish Echoes column of the April, 2024 edition of Blue & Gold Illustrated)

Donate

Support the work of the Knute Rockne Memorial Society with a tax-deductible donation today.

Subscribe

Join our email list to receive the latest news and posts from the Knute Rockne Memorial Society.