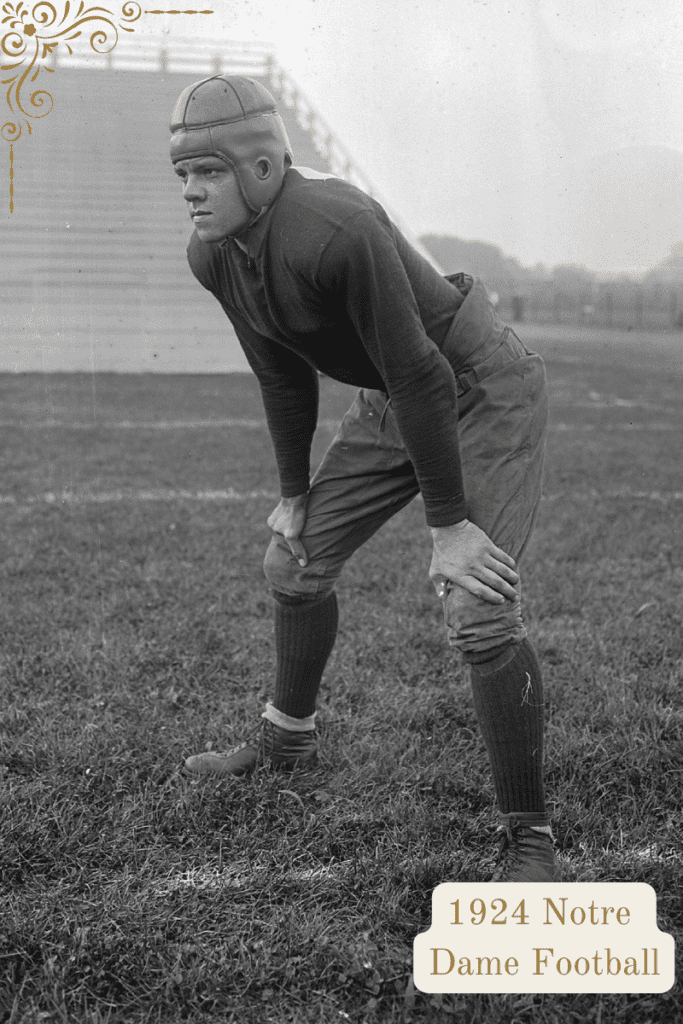

Chuck Collins

Left End

Oak Park, IL

St. Ignatius High School was founded in 1869 as Chicago’s first Jesuit school. The original St. Ignatius building, crafted in Second Empire style, is one of only five existing Chicago structures to predate the Great Fire of 1871.

Chuck Collins was not the biggest name on the 1921 St. Ignatius football team – that would be fullback Bill Cerney, who was committed early to taking his talents to Notre Dame. Collins’ future wasn’t as clear. His father James was a successful businessman who believed college was a waste of time and money; you graduated high school and went to work. Finally, the elder Collins was convinced to let Chuck head to South Bend.

Cerney, for his part, would also go on to play a vital role for the Irish, as fullback on the Shock Troops, who started every game of the season. He scored three touchdowns to finish sixth on the ’24 team in scoring with 18 points. He is sometimes referred to as “the Fifth Horseman.”

Before arriving at Notre Dame, Chuck Collins had already proved his mettle as a tough, resourceful, courageous fellow. That reputation was cemented on a late February Sunday afternoon in 1918, when the 14-year-old Collins set off on an adventure with younger brother Ed, then 12, and two of their pals.

The foursome took the streetcar line until it ended, then walked several blocks to reach the Forest Preserve that runs along the Des Plaines River. Their mission was to explore the woods, the swamps and the river itself, which ran swiftly underneath the winter ice. At one spot, though, the ice gave way and Ed Collins found himself in the freezing water, fighting for his life.

“I called for help and then went down,” Ed recalled years later. “The next time I came up, I saw my brother hurry across and leap into the ice-cold water after me. When I was going down for the second time, I felt his grasp around my stomach and the next moment I was on top of the ice by my brother’s side.” Aided by their two friends, the brothers made it safely to nearby shoreline.

And in a game for St. Ignatius, Chuck Collins had his right hand ripped open when a set of cleats landed on it. His index finger became infected and had to be amputated. At a time when Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown was the star pitcher of his Chicago Cubs, Collins overcame a similar disability to be a star athlete in football and basketball.

As a Notre Dame sophomore in 1922, Collins backed up team captain Glen Carberry at left end, before taking over as the regular in 1923. He was poised for a big season in 1924 and didn’t disappoint. In the epic game with Army on Oct. 18, 1924, at the Polo Grounds in New York City, Notre Dame was protecting a 6-0 late in the first half when Army was driving. But Collins broke through the Cadet line and batted down a pass to thwart the drive.

The Scholastic’s Football Review praised Collins with these words: “Collins never once has failed in his duty on the left flank and deserves to be remembered with the great ends in football history.

“He performs his work silently. He has mastered the fundamentals of his position and directs his every movement for the benefit of the team. He has faced good competition for the flank berth, but always he has been found dependable, ever aggressive and a man with a true fighting heart. He is as good on the offense as he is on the defense, receiving passes and forming interference for the ball carriers. With exceptional speed he goes down under punts and seldom fails to get his man.”

Collins, Cerney and other team members from Chicagoland had circled the Nov. 22 game at Northwestern as a homecoming of sorts. Just days before the game, the site was changed from the campus field in Evanston to the newly constructed (and not yet finished) Grant Park Stadium, later to be named Soldier Field.

There, in the first major sports event at the massive new stadium, 45,000 gathered to watch what became Notre Dame’s closest game all season. Clinging to a 7-6 lead in the fourth quarter, the Irish were hard-pressed to hold off the determined Wildcats. It took an interception by Elmer Layden returned 45 yards for a touchdown to secure the 13-6 victory and keep Notre Dame unbeaten.

In the Rose Bowl against Pop Warner-coached Stanford, Notre Dame held a 13-3 third quarter lead when Layden launched a 50-yard punt into the waiting arms of Stanford’s Fred Solomon. But the Cardinal quarterback bobbled the ball and it bounced away from him. Solomon dove for the ball, but Chuck Collins brushed him aside and Irish end Ed Hunsinger flew past, picking up the ball and racing 20 yards for a decisive touchdown in the 27-10 victory that clinched the national championship.

After graduation, Collins spent a year as line coach at Chattanooga, then took over as head coach at North Carolina, where he guided the Tar Heels to 38 victories over the next eight seasons. By far the best year was 1929, when Collins’ team went 9-1, losing only a 19-12 decision to Georgia. The Tar Heels outscored the opposition, 346-59.

Not many teams had a better record than Carolina that year, but one of them was Notre Dame at 9-0. And at left end for Rockne’s national champions? The young man who owed his life to his courageous older brother – Ed Collins.

Upon his death in 1977 in Ridgewood, New Jersey, fellow Monogram Club leader Joseph Abbott said: “Chuck Collins was regarded not only as a great athlete but also one of the most outstanding alumni of our great university.”

Donate

Support the work of the Knute Rockne Memorial Society with a tax-deductible donation today.

Subscribe

Join our email list to receive the latest news and posts from the Knute Rockne Memorial Society.