In March of 1931, Knute Rockne was riding high. The 43-year-old product of Chicago’s Northwest Division High School and former mail clerk at the Chicago Post Office had become one of the most prominent Americans of his time.

For 13 seasons, his University of Notre Dame football teams won with stunning regularity, earning three consensus national championships, including those of 1929-30. The Fighting Irish owned a 19-game winning streak.

Rockne was in constant demand as a speaker. He traveled to consult with others in athletics and business, and spent weeks each summer conducting “coaching schools” on college campuses nationwide, from Williamsburg, Va., to Corvallis, Ore. The Studebaker Corp. of South Bend had hired Rockne as vice president of sales promotion, and he traveled the country in football’s off-season to rally the carmaker’s sales force.

In late March, he was headed out to Los Angeles with a multi-purpose schedule. He was going to meet with film studios about a proposed picture celebrating Notre Dame football. There were speaking engagements, including a joint appearance with his great friend Will Rogers. Rockne would represent Chicago’s Wilson Sporting Goods at a store opening; and meet with some Studebaker dealers.

On the evening of March 30, he stopped at his mother’s place in Logan Square to help celebrate her birthday, then boarded a night train for Kansas City. From there, he would fly to Los Angeles.

Innovation and Peril of Early Air Travel

Rockne knew that the rapid development of air travel in the 1920s had been fraught with danger and conflict. Aviation pioneers and stunt pilots straddled the line between testing the limits of the new technology—and death. And already, there was significant tension between the federal government’s dual roles promoting air travel and ensuring its safety.

Meanwhile, in Europe, Anthony Fokker had become one of the best-known names in early aviation, rising to prominence as a builder of biplanes used extensively by Germany in the Great War. But reluctance to invest in research and development led to his struggles with quality control throughout his career. Flaws in both design and workmanship were traced to Fokker’s apparent insistence on using the cheapest materials and methods.

When Fokker set up shop in the U.S., his F-10 tri-motor plane drew the attention of government officials; they were concerned about not being able to inspect the internal structure of the wings because it would involve removing the plywood covering and damaging the craft. The U.S. Navy tested the F-10A, found it unstable and rejected it. However, it still found a place in early commercial aviation.

Rockne’s Final Flight

On the morning of March 31, Rockne and seven other men flew out of the Kansas City Municipal Airport aboard Transcontinental & Western Airlines flight 5. The Fokker F-10A had been inspected a few days earlier by a TWA mechanic who later noted that “the (plywood) wing panels were all loose and it would take them days to fix it, and I said the airplane wasn’t fit to fly and I wouldn’t sign the log. Nobody was safe in that airplane.”

Off it went anyway, but to reach its first stop at Wichita, Flight 5 would have to penetrate a sharp cold front and thick clouds, fog, ice, and low ceilings. An hour into the flight, its pilots radioed Wichita that “the weather here is getting tough. We’re going to turn around and go back to Kansas City.” But the Wichita station encouraged the flight to continue as planned.

The pilots responded: “It’s getting tighter. It looks pretty bad.” The flight had drifted off course, requiring navigation via the “Old Iron Compass“—the railroad track below. The pilots were now “too busy” to talk; they were likely squinting through rain-slicked windshields, trying to follow the rail tracks just 300 feet or less below.

A deadly situation was developing; the clouds were almost touching the hilltops. Once the crests disappeared, the Fokker would be trapped and the option of climbing to at least temporary safety forfeited, since to do so would involve a good probability of crashing into the hidden higher ground. They were being squeezed between the ground and the clouds. The failure of instruments due to icing compounded the danger.

Deprived of key references, the disoriented pilots would have been unable to keep the airliner from entering a spiral dive. The Fokker was now out of control, nose down and accelerating. When screaming engines and runaway tachometer readings alerted the pilots to their predicament, they would have pulled the throttles right back, producing the backfiring heard on the ground seconds before the airplane crashed in a pasture. All eight aboard died instantly.

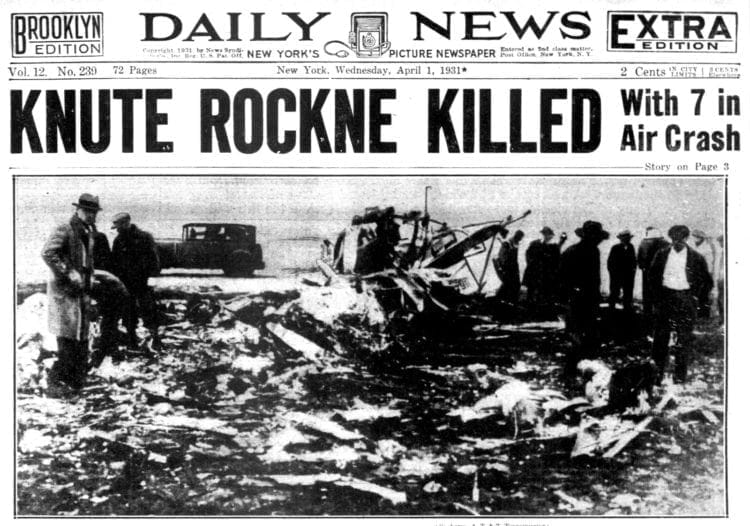

Newspaper headlines nationwide screamed, “Rockne Killed in Air Crash.” For the first time, an airline accident claimed the life of a prominent American. The public was outraged and wanted answers that weren’t immediately forthcoming. The crash site had been unsecured for hours and became a haven for souvenir collectors. In the ensuing days, the Aeronautics Branch of the U.S. Department of Commerce issued conflicting statements about a possible cause. Finally, crash investigators focused on deterioration of the wooden wing spar, finding evidence of delamination and failed joints. One wing had completely separated from the plane.

A Lasting Impact on Flight

Rockne’s crash had an immediate and lasting effect on aviation. It was said the industry could not have had worse publicity “had the victim been the President of the United States himself.” All F-10s and F-10As were barred from carrying passengers until they were thoroughly inspected. The American market for Fokker’s wooden-winged planes was immediately and permanently gone. Even the all-metal Ford Trimotors were doomed, due to their resemblance to the “plane that killed Rockne.”

The Rockne crash eventually led to the design and manufacture of the Douglas DC-2, the first airliner built using all-metal, stressed-skin construction, and a host of other innovations. It, along with the DC-3, provided the safety and comfort, combined with economy that allowed the swift expansion of the worldwide passenger airline industry as we know it today.

The role of government in requiring safer planes also took off. Spurred by the crash of March 31, 1931, the Aeronautics Branch took on greater duties in certifying aircraft and regulating the industry, and in 1934 was renamed the Bureau of Air Commerce to reflect its enhanced status within the Commerce Department. In 1940, it was split into the Civil Aeronautics Administration and the Civil Aeronautics Board; eventually it became today’s Federal Aviation Administration.

It took the crash that killed Rockne, and another four years later that claimed Will Rogers and aviator Wiley Post, to create a much more vigorous role for the federal government in airline regulation, aircraft safety and crash site security, investigation and reporting.

Today, 90 years later, we reap the benefits that came out of tragedy.

Jim Lefebvre is the author of the national award-winning biography Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne and executive director of the Knute Rockne Memorial Society.