Coach Knute Rockne and his Notre Dame football squad came into the 1920 season on the heels of a perfect mark of 9-0-0 in 1919, with another challenging schedule lined up, and great hopes for continued success.

The fall of 1919 had brought a return to normalcy on campus after two years disrupted by the Great War and the Spanish Flu. Here’s how the Scholastic put it: “We are better for having experienced (the war and flu) and we know now something we did not realized before—the vast advantages that are ours. With the beginning of 1919, we start a new era in our school and in our lives.”

The feature game in 1919 had been the trip to West Point, where Army held a 9-6 lead late in the third quarter. But George Gipp, as he so often did, rose to the occasion, hitting Eddie Anderson on the dead run with a perfect pass for 26 yards to the Army 7. Walter Miller drove over two plays later for the winning score—a final of 12-9, ND. “The Notre Dame timing is uncanny,” wrote one observer. “And their new coach is obviously a master in the small details that spell the difference between success and failure in a play.”

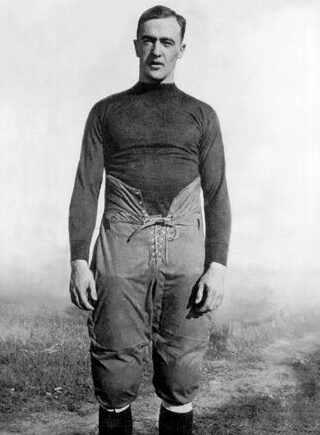

Gipp finished the season with staggering numbers: 729 yards rushing and 727 yards passing, and was a terror on defense as well, leading the team with three interceptions. He gained deserved recognition by several All-American teams, yet not those from the East, such as Walter Camp’s.

The biggest victory for 1920 might have been secured before the season, when Gipp returned to campus in late September. Over the previous months, his billiards championships and all-night poker games took a toll on his schoolwork, and he was asked to leave ND in the spring of 1920. But the businessmen around town delivered a smart, well-written petition to the school to give the star one more chance, and he was re-admitted.

One repercussion of Gipp’s spring semester was the loss of the Irish captaincy of 1920. In the team vote following the 1919 season, Gipp edged out tackle Frank Coughlin for the honor. In Gipp’s absence, Coughlin was elevated to the captaincy, and Rockne decided that’s how the season would proceed.

Other key returnees included Gipp’s right-hand man from Upper Michigan, Heartley (Hunk) Anderson at one guard; Maurice (Clipper) Smith at the other guard; and ends Anderson and Roger Kiley. Little Joe Brandy (5-8, 147) took over at quarterback and strong reserve backs Norm Barry and Chet Wynne stepped up to first-string roles astride Gipp.

The season’s two biggest trips fell two weeks apart in October, to Nebraska and Army.

On Oct. 16 at Lincoln, the Irish were clinging to a 9-7 lead in the fourth quarter when Gipp hit Barry with a pass to the Huskers’ 20. On the next play, Gipp executed a perfect fake pass, then broke free and ran for the clinching touchdown in the 16-7 win. Gipp and his teammates impressed the locals. “The gameness of the visitors delighted the 10,000 who jammed the park,” read one account.

October 30 brought the annual Army game at West Point. The Cadets led 17-14 at the half, and Rockne railed on the team for its sloppy play, but Gipp assured his teammates, “You guys give me a little help and I’ll beat this Army team.”

And that’s how the second half went, with Gipp gaining consistently on rushes, and flinging passes to Kiley and Johnny Mohardt. He played the decoy as Mohardt crashed over for the winning touchdown, then led another brilliant drive, with another pass to Kiley setting up a rushing touchdown. The 27-17 victory sent the Eastern press into a tizzy.

“George Gipp is an All-American, or there are no real All-Americans this season,” noted the New York Herald Tribune. “If anything can be done on a football field that Gipp didntt do yesterday, it is not discernable to the naked eye.”

The Irish returned home to crush Purdue, 28-0, before a record crowd of 12,000 at Cartier Field, with Gipp accounting for a staggering 257 total yards, including 129 rushing yards on just 10 carries. The following Saturday, despite sporting a severely injured shoulder, Gipp came off the bench to lead Notre Dame to a comeback, 13-10 victory over Indiana at Indianapolis, the team’s closest call of the season.

On Nov. 20, 1920 one of the greatest football players of all time, George Gipp, made his final appearance on a gridiron.

Rockne’s undefeated squad was taking on Northwestern at Evanston; Gipp was not only hurt, but suffering from persistent tonsilitis. Rockne had come to his star prior to the game and told him he planned to rest him that day. “That’s jake with me,” came Gipp’s response.

A crowd of 20,000, including thousands of ND fans, packed Northwestern Field. When it became obvious Gipp wasn’t playing, they booed Rockne mercilessly and chanted, “We want Gipp! We want Gipp!”

Finally relenting, Rockne sent Gipp into the latter stage of the game, expecting just a token appearance. But that wasn’t Gipp’s way. Somehow, he found the strength to deliver a 35-yard TD pass to Anderson, then a 55-yarder to set up another score, sealing a 33-7 victory.

Gipp’s stats for 1920 are awe-inspiring. He appeared in eight games, some only partially, yet gained 827 yards on 102 rushing attempts (an average of 8.11 yards per attempt, still a record) and added 709 yards passing. His total-offense average of 9.37 yards per play is also still tops in ND history. He scored 64 points on 8 touchdowns and 16 extra points. He played his best in the biggest games—the wins over Nebraska, Army and Purdue—and when needed most, as in the comeback vs. the Hoosiers.

Three days after the Northwestern game, Gipp was admitted to St. Joseph Hospital with a temperature of 104. He was apart from his team when they concluded the season against the Michigan Aggies at East Lansing on Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 25, 1920, in what might be called the original “Win One For the Gipper” game.

Rockne’s team, undefeated at 8-0, traveled north without Gipp, seriously ill in St. Joseph Hospital, to take on the Michigan Aggies. It had been an up-and-down season for MAC: in their four victories over Albion College, Alma College, Olivet College and the Chicago YMCA, the Aggies had outscored the opposition, 254-0. But against major teams, MAC had lost to Wisconsin (27-0), Michigan (35-0) and Nebraska (35-7).

Even without Gipp, ND featured many outstanding players, including Joe Brandy, Norm Barry, Chet Wynne, Roger Kiley and Eddie Anderson. But on this day, Rockne implemented his new strategy: starting a lineup of backups, called the Shock Troops, while holding back his regulars for a quarter or more.

The Shock Troops struck quickly when reserve halfback Danny Coughlin, from Waseca, Minn., returned the opening kickoff 90 yards for a touchdown. And while it was reported that the record crowd of 8,000 “was disappointed by the absence of Gipp from the Notre Dame lineup,” they saw a competitive first half that ended 6-0.

It was another backup from Minnesota, sophomore fullback Paul Castner of St. Paul who stood out in the second half, scoring two TDs to help secure a 25-0 ND victory. Castner, sometimes called the Fifth Horsemen, would go on to a stellar career including playing with the famous backfield in 1922. He was also player-coach of the Irish hockey team, and star pitcher in baseball.

Rockne’s squad gained acclaim as “Western Champions” of 1920. The victory gave Rockne an overall record of 21-1-2 in his three seasons as ND head coach, for a winning percentage of .917. His teams had not lost since Nov. 16, 1918—a 13-7 defeat to the Aggies on the same field.

But while Rock’s men could celebrate these and other honors, their star player lay seriously ill at St. Joseph Hospital.

If it happened a few years later, Gipp’s case of tonsillitis and then strep throat could have been easily treated with a course of antibiotics. Instead, he endured a series of setbacks, interspersed with rallies. Dramatic daily dispatches about his condition were sent from South Bend and made news across the nation. Gipp would slip into a coma, then rally.

On Sunday, Dec. 12, and again the next day, Gipp was alert enough at times to speak with family members, Dr. James McMeel, Coach Knute Rockne, and his teammate and long-time friend Hunk Anderson. But the prognosis was grim. “A thousand words couldn’t describe what I saw in his face,” Hunk later said. “For the first time since his illness began, I, too, didn’t think he’d make it.”

After the end came, at 3:30 a.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 14, the night clerk at the Oliver Hotel, where Gipp sometimes lived and regularly reigned as champion billiards and poker player, switched the hotel lights on and off three times, a pre-arranged sign to the night staff that their dear friend George Gipp was gone.

Portions of this piece are reprinted from Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne, by Jim Lefebvre (2013, Great Day Press).

Jim Lefebvre is the author of the national award-winning biography Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne and executive director of the Knute Rockne Memorial Society.